Like other dipole moments, the transition dipole refers to a difference in charge from one region of a molecule to another. The transition dipole occurs when an electron is excited from the ground state to an excited state. The charge distribution of the ground state is different from that of the excited state, and it is this change in electron density between the two states that leads to the transitoin dipole.

Transition

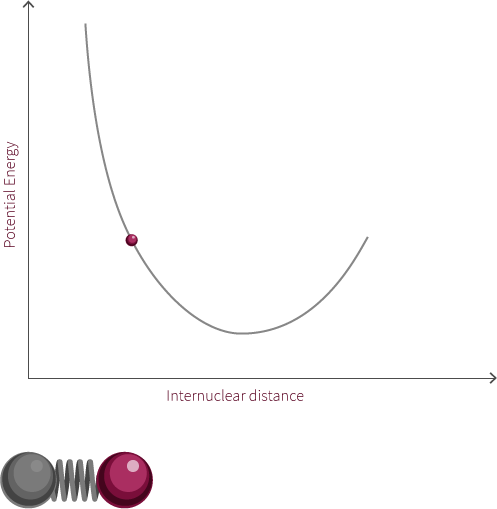

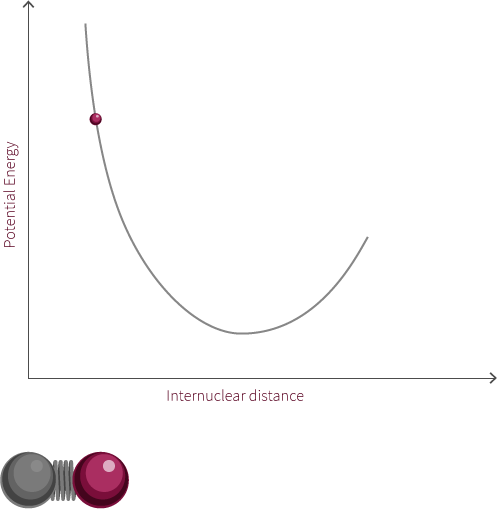

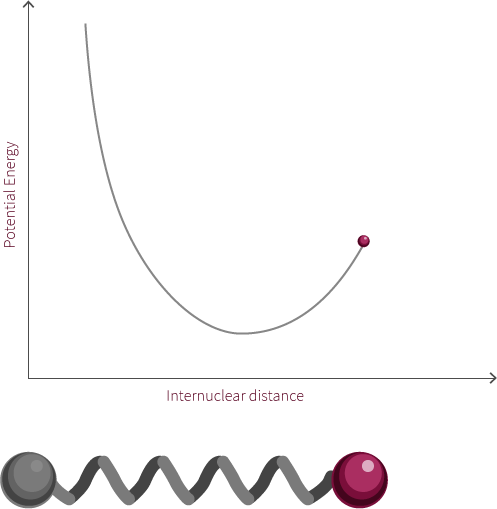

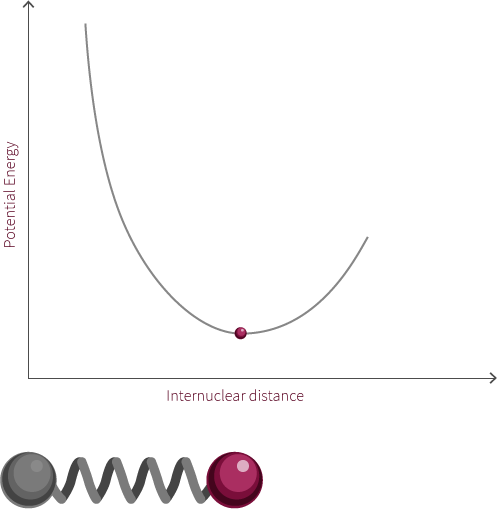

In our example of the diatomic molecule, as seen above, you can see a proposed transition for an electron from the π to a π* molecular orbital. As can be seen, the π* orbitals on the right side of the molecule has greater electron density further way from nucleus than the ground state π, and it is in this direction that the dipole points.

The transition dipole’s orientation is extremely important for determining whether or not molecular excitation occurs. In order to excite an electron from its ground state to an excited state not only must it be supplied with the right amount of energy by a photon to make a transition to an allowed state, but the electric field of the photon must also align with the transition dipole in order for excitation to take place. When a photon of light promotes an electron to an excited state all of its energy goes into the event and is said to be absorbed. This process is called absorption.

In the example to the left, the π* orbitals have a different electron density than the π system. We have altered the electron density between the lobes of the π* orbitals, and the dipole arrow aligns with the orbital lobe with the greatest electron density. Alignment between the transition dipole and electromagnetic field does not have to be perfect. However, the probability that a photon will be absorbed decreases as the angle between the transition dipole and electric field increases.

Transition Photon

Generate more transition dipoles and look at the properly aligned photon. Is there anything you notice about these proposed transition dipoles?